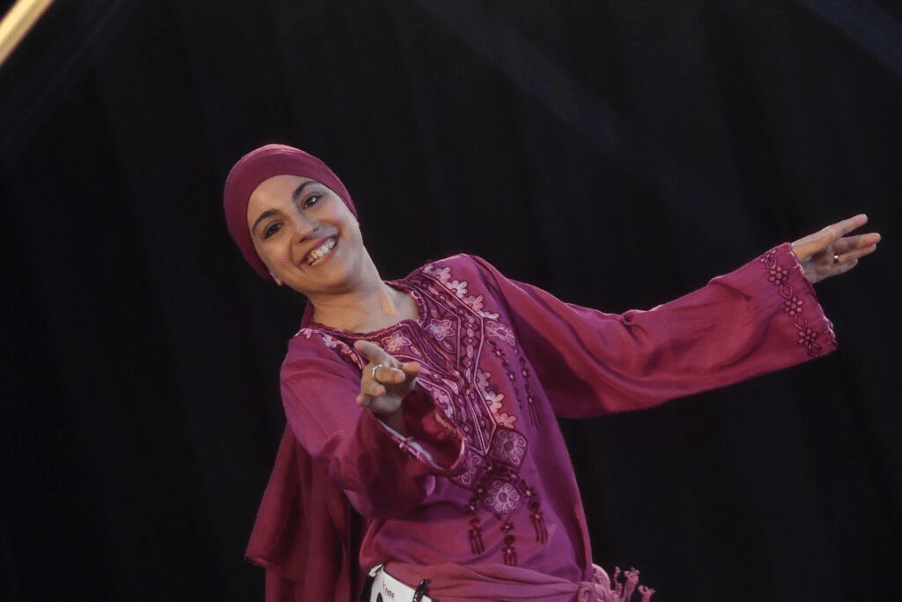

I always knew that sooner or later dance would become an important part of my life. When I was twenty-three and had the opportunity to study this sublime art, it was crystal clear: Arab dance was the one for me. I was studying Arabic and in my first year of Islamic studies at the L’Orientale University of Naples. I had returned from Damascus a few months earlier wearing a veil on my head, or better, hijab. My life as a Muslim had just begun and I was trying to figure out how to proceed, now that people were looking at me differently and my habits and way of being in the world had changed.

Umayyad Mosque, Damascus, my photo

I needed a language for expressing my experience, an art form that could give meaning to the chaos, the one that I’d always felt a kinship with: dance, which is for me first and foremost a way of listening to music and in general the sounds that surround us. I had experienced the importance of sound in Damascus, struck by the call to prayer but even more by the recitation of the Koran, which I have already written about here.

I knew little about eastern dance, which is sometimes called belly dancing or Arab dance. In my imagination it was tied to spangles and sensuality, and I was struck by how in Syria the word raqqasa, meaning professional dancer, also means immoral woman. I had learned a lot in Damascus about modesty and the need to cover one’s body, being alert to male bodies, so where did dance fit in? At weddings and in homes among women, as I later saw elsewhere in the Arab world, but for me as a European, dance was first and foremost a performance art, an artistic language that needed an audience and a stage.

Mahmoud Reda and Farida Fahmi

During my first eastern dance lesson, I learned that the origin of this art form is for the most part unknown, but one thing is certain: the Arab world kept it alive, in particular Egypt, which defined its styles and technique, especially thanks to the work of the dancer and choreographer Mahmoud Reda. Thanks to Reda, Arab folklore came into contact with theatre, a typically western form of narrative, but one that allowed dance to expand beyond its boundaries. At the same time, cabaret dance emerged, to please a varied audience, especially the English, and so Arab culture reckoned with the ‘Orientalist’ gaze. We talked about this with Claudia Lunetta and Jolanda Guardi here.

This story was in a certain way mine, as well, and I needed to reckon with it. At first, I decided to devote hours of practice in the dance studio and at home. I did it for myself, to know the Arab world from a different perspective, and little by little it became my personal means of expression. I only went on stage for the end-of-year show with my female companions. I was Muslim, I wore the veil, they told me one does not dance in public and I asked no questions.

My first national competition, in 2022, Oriental style, Italian champion, FIDS (Federazione Italiana Danza Sportiva – Italian Federation of Dancesport) class C 31-49

The years passed, I moved to Germany and I tried other types of dance out of curiosity and to enrich what always and in any case seemed to be my favourite artistic language. I feel at home in Middle Eastern dance, like in the Arabic language. Dance is a discipline that requires humbleness, effort and patience, important qualities for all Muslims. I find numerous affinities with Islamic practice, and yet there is a lot of controversy surrounding this art.

At a certain point, the time came for me to step on stage before an audience and I rediscovered a fundamental principle of Islam: the importance of intention, niyya. If it took me ten years to find the harmony between my personal expression, the respect at the origin of eastern dance and Islam, it’s because purifying the intention behind every movement is no easy task, but a long, sometimes painful, process.

My first national competition in 2022, Folk Oriental style, Italian champion, FIDS (Federazione Italiana Danza Sportiva – Italian Federation of Dancesport) class C 31-49

The stage is no different from the other spaces of our lives: whether city streets, the workplace or social media, whenever our body connects with the outside, we need to remember that it is better to share than to show, that it is more valuable to inspire emotion than to receive applause, that every effort is in vain if it is not in the service of the common good, that for believers every action is dedicated to God and not our personal pleasure.